The Jesus Prayer, known in its most common form as “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner,” stands as one of the most ancient and revered prayers in the Holy Ancient Orthodox Church. It is not a formula invented for convenience, nor a casual repetition of words for sentimental comfort. It is the distillation of the Gospel’s entire message. It is a spiritual weapon, a lifeline of the soul, and the heart of true hesychasm—the path of stillness and prayer leading to union with God. This article will examine its roots, meaning, scriptural foundation, liturgical significance, and its role in the ascetic life.

Origins and Scriptural Foundation

The Jesus Prayer is not an invention of monastics or a product of medieval mysticism. It is not a construction born of psychological needs or a liturgical flourish devised by later centuries. It is drawn directly from the Word of God and organically developed within the Church’s ascetical life, grounded entirely in the Scriptures and the lived experience of holiness.

The phrase “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner” finds its origin most explicitly in Luke 18:13, where the publican—standing afar off, not daring to lift his eyes to heaven—struck his breast and cried, “God, be merciful to me, a sinner!” The Lord Himself affirms the superiority of this prayer, stating: “I tell you, this man went down to his home justified rather than the other” (Luke 18:14). This prayer, though brief, contains the very essence of repentance: an acknowledgment of personal sin and a plea for divine mercy. In the Gospels, the blind men by the roadside who cry out, “Jesus, Son of David, have mercy on me!” (Matthew 9:27; Luke 18:38) are not engaged in formulaic piety. They are invoking the Messiah by name, appealing to Him not for abstract favours, but for healing—physical and spiritual. This appeal to Jesus by His proper title and the cry for mercy are both mirrored directly in the Jesus Prayer. In their desperation, faith, and persistence, they exemplify the very posture that the Prayer demands: urgency, humility, and faith.

The invocation of Jesus’ name is not an optional aspect of piety. It is commanded. St. Paul writes, “No one can say ‘Jesus is Lord’ except by the Holy Spirit” (1 Corinthians 12:3), thus affirming that even the articulation of Christ’s Lordship requires divine assistance. It is a statement not of information, but of allegiance and worship. When the Church confesses “Jesus is Lord,” it is not mimicking an abstract creed—it is bending the knee of the soul.

Again, the Apostle writes, “At the name of Jesus every knee should bend, in heaven and on earth and under the earth” (Philippians 2:10). The name is not a label—it is power, it is presence. In Orthodox theology, the name of Jesus is not detached from His person. When we invoke His name, we are not referring to Him in absentia—we are encountering Him. To speak His name with faith is to enter into His presence. This is why the demons tremble when His name is spoken with authority, and why the saints weep when it is uttered with love.

The Orthodox Church did not fabricate the Jesus Prayer as a mechanical formula. It was received—by prayer, through suffering, in the desert. The Desert Fathers, beginning with St. Anthony the Great and his successors—St. Macarius of Egypt, St. Arsenius, St. John Climacus—practised inner prayer long before the prayer was codified in words. Their goal was not emotional comfort but watchfulness (νῆψις), the guarding of the heart. By the time of the Philokalia, this tradition had matured into a rigorous and articulate theology of inner prayer. St. Gregory of Sinai, St. Nikephoros the Monk, St. Kallistos and St. Ignatios Xanthopoulos, and later St. Theophan the Recluse, gave shape to what had already been lived for centuries. They did not invent a practice; they preserved one. They wrote not to innovate, but to hand down (παράδοσις) what they had received.

The Jesus Prayer is therefore not an esoteric method. It is not for curiosity. It is not spiritual gymnastics. It is a sacred inheritance (ἱερὰ παράδοσις). It was never designed for experimentation, nor for self-exploration. It is designed for one purpose. That purpose is repentance. It is the continual cry of the tax collector. It is the ongoing plea of the blind man. It is the prayer of the thief on the cross: “Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingdom” (Luke 23:42). It is given for one reason. That reason is divine mercy. This mercy is not sentimental tolerance. It is the healing of the soul, the forgiveness of sins, the cleansing of the conscience. It is the beginning of sanctity and the end of all striving. The purpose of the Jesus Prayer is the purification of the heart. As the Lord said: “Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God.” (Matthew 5:8) There is no other way. Doctrine without repentance is cold and dead. Ritual without inner contrition is lifeless. The Jesus Prayer purifies because it forces the soul to confront itself before God, not with abstractions, but with urgency.

Let the words be few. Let the tears be many. Let the repetition be not vain, but filled with meaning. The name of Jesus, spoken in truth, cleanses the mind, calms the passions, and draws down grace. This is not mysticism—it is Orthodoxy. This is not innovation—it is ancient practice. This is not optional—it is necessary.

Text and Form of the Prayer

Let us now consider the form and substance of the Jesus Prayer in its various articulations, paying close attention to why the full version is both doctrinally sound and spiritually superior according to the teaching of the Holy Fathers.

The Standard Form and its Components

The complete and preferred form of the Jesus Prayer is:

“Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner.”

Obviously this prayer is not long, but every word is weighty with theological meaning and spiritual force. The Church has preserved this phrasing through through the blood and tears of saints and martyrs who lived and died in repentance and unceasing prayer. Each part is a confession of the Orthodox Faith, a blow against pride, and a plea for divine mercy.

“Lord Jesus Christ”

To call Jesus “Lord” is to recognise His divine sovereignty. The Greek word Kyrios (Κύριος) is the Septuagint rendering of the Tetragrammaton—YHWH (יהוה). Thus, to call Jesus “Lord” is to proclaim His divinity, not as a metaphor, not as a courtesy title, but as a confession that He is God. This title is not honorary; it is dogmatic. “If you confess with your lips that Jesus is Lord and believe in your heart that God raised him from the dead, you will be saved.” (Romans 10:9) The Syriac version of the New Testament, called the Peshitta, renders this verse as: “If you confess with your lips that Jesus is Yahweh…” There is no salvation without this confession. To speak the name Jesus (Ісусъ) is to name the One who saves. The angel commanded Joseph: “You are to name him Jesus, for he will save his people from their sins.” (Matthew 1:21) The name itself means “Yahweh saves.” In invoking His name, we invoke His very identity and mission which is the salvation of sinners. This is not a name that may be passed over. “There is salvation in no one else, for there is no other name under heaven given among mortals by which we must be saved.” (Acts 4:12) To call Him Christ is to affirm that He is the Anointed One foretold by the prophets, the fulfilment of Israel’s hope, the Messiah who came not to overthrow the Romans but to crush the tyranny of sin and death. It affirms both the continuity of the Old Testament and its completion in the New.

Thus, the first part of the prayer—“Lord Jesus Christ”—is not a string of titles. It is a confession of the Faith handed down from the Apostles. It contains the entire Creed in miniature.

“Son of God”

This is a direct affirmation of Christ’s divine origin and eternal relationship with the Father. He is not a son, like the angels or kings of old. He is the Son, begotten of the Father before all ages. In saying “Son of God,” the one who prays is professing the Nicene Faith, which anathematises all who deny the true divinity of the Son. This part of the prayer also points to the mystery of the Incarnation. The Son of God became man, taking flesh from the Virgin Mary by the Holy Spirit, becoming what He had not been without ceasing to be what He always was. The demons called Him “Son of God” in fear. The Church calls Him so in reverence.

By including this in the prayer, we are not only professing doctrine—we are identifying the One who alone can have mercy—the God-Man, Jesus Christ.

“Have mercy on me”

This is the central plea of the Gospel. It is the heart-cry of the publican, the leper, the Canaanite woman, the blind beggar. Mercy is not a casual pardon. It is a cry for healing, for the removal of sin’s stain, and for reconciliation with God. It is the plea of the heart that has seen its own corruption and knows it cannot stand before the Judgement Seat unless clothed in grace. To ask for mercy is to acknowledge one’s absolute dependence upon the Creator of the universe. It is the death of pride. The one who seeks mercy is the one who has come to know his own bankruptcy.

Mercy is also God’s condescension toward the penitent. In the Septuagint, the Hebrew hesed—God’s covenantal loving-kindness—is translated as mercy. Thus, the prayer is not only asking to be forgiven but to be drawn into God’s steadfast love.

“A sinner”

We should never think of this as a rhetorical flourish. This is not a general admission shared by all mankind. This is a personal, concrete acknowledgement: “I am the sinner.” Not others. Not humanity in abstract. Me. For example, the saints tell us that we should think of ourselves as the worst among sinners. This is not exaggeration. This is truth. When you have seen your heart as it truly is, you will not concern yourself with the sins of others. When you say “a sinner” in the Jesus Prayer, you are placing yourself at the foot of the Cross—not beside Christ as a spectator, but as the thief who says, “We are getting what we deserve… Jesus, remember me.” (cf. Luke 23:41–42)

The Fathers insisted on this final part. It breaks the back of self-righteousness. It is a sword against spiritual vanity. It empties the soul so that grace may enter.

Shorter Forms and Their Use

While the shorter forms—such as “Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on me,” or “Jesus, Son of God, have mercy”—retain portions of the theological content, they lack the full articulation of the truth. They may be used by beginners, the infirm, the dying, or in moments of extreme need. Even a cry of “Jesus!” spoken with faith is heard in heaven. However, the Fathers, especially St. Gregory of Sinai, insisted that the full form is to be used whenever possible. It contains within it the full confession of faith, repentance, and supplication. It is not more words that matter, but the fullness of meaning.

Theological Summary

This prayer is no ordinary utterance. It contains:

- A profession of faith in the Holy Trinity (by implication through the Son),

- A confession of Christ’s divinity and humanity,

- An acknowledgment of personal sinfulness,

- A plea for God’s mercy grounded in the Incarnation and Cross.

It is not merely a prayer; it is a lifelong ascetical path, and it is why the Orthodox Church of Christ holds it as sacred. The one who recites it from the heart walks the narrow road. The one who lives by it shall not be put to shame at the Judgment.

Theological Significance

Let us now examine in full the theological and ascetical implications of the prayer, dealing with the spiritual operation of the Jesus Prayer, not as magical incantation, but as holy invocation. The Fathers of the Church are emphatic on this point: the Jesus Prayer is not magic. It has no mechanical power. It is not efficacious by utterance alone. It is not a charm. It is not a ritualised formula that compels divine favour or spiritual success. God is not manipulated. Grace is not summoned by technique.

The Jesus Prayer is not a talisman. The beads are not relics of superstition. The repetition is not vain babbling, which our Lord warned against (cf. Matthew 6:7). Rather, the prayer is a participation in the Name of the Lord, and that participation is personal, moral, and ecclesial. “The name of the Lord is a strong tower; the righteous run into it and are safe.” (Proverbs 18:10) But it is only the righteous who may enter. This is no automatic protection. It requires humility and repentance.

Participation in the Name

To invoke the Name of Jesus is to call upon Him, to make oneself present before Him. The Name is not separate from the Person. This is the clear teaching of the Fathers. St. Gregory Palamas insists that the energy of God is present in His name—not the essence, which is inaccessible, but the energy by which He acts in the world. To speak the Name in faith and fear is to enter into His presence.

The aim of the Prayer, then, is not relaxation, not a tranquil emotional state, not a mystical vision. It is attention—not general awareness, but focused spiritual sobriety. The heart must be kept awake. The mind must descend into the heart. This is the teaching of St. Theophan the Recluse and St. Nicephorus the Hesychast. When the mind joins to the heart, there begins the true work of prayer. When our attention is real, it gives birth to contrition, a broken and humbled heart. The aim is not self-esteem but compunction. “The sacrifice acceptable to God is a broken spirit; a broken and contrite heart, O God, you will not despise.” (Psalm 51:17) Prayer without tears is dry. Repetition without repentance is useless.

This is why the repetition of the Jesus Prayer is not vain. It is not the quantity that matters, but the quality of heart that each repetition builds. The repetition is the rope that lowers the bucket into the well of the heart. Eventually, if not at once, the water of compunction is drawn up. This is the path to what the Apostle commands: “Pray without ceasing.” (1 Thessalonians 5:17) This is not hyperbole. It is the literal aim of Orthodox spiritual life.

The Name as Sword and Shield

St. Hesychius of Jerusalem writes: “Rebuttal bridles evil thoughts, but the invocation of Jesus Christ drives them from the heart.” This is no poetic exaggeration. The Fathers speak from experience. The demons flee from the Name, not because of the sound, but because of the presence of the One who is named. Demons endure piety. They endure long services. They endure fasting. But they cannot endure true prayer offered in humility, especially the Jesus Prayer. The Name, spoken with faith, becomes a sword.

St. John Climacus writes in the Ladder: “Flog your enemies with the Name of Jesus, for there is no weapon more powerful in heaven or on earth.” And again, St. Barsanuphius teaches that demons are burned by the invocation of the Lord’s name, but they return if the one praying becomes proud. Thus, the prayer is a shield as well—but only when it is coupled with humility. Without humility, even sacred things become dangerous.

A Safeguard Against Pride

The Jesus Prayer is also a safeguard against spiritual delusion. It reminds the soul, continually, of its state before our Creator—a sinner in need of mercy. It casts down thoughts of grandeur. It drives away demonic suggestions of self-righteousness. There is no room for arrogance in the one who repeats, “Have mercy on me, a sinner” with every breath. If pride creeps in, the prayer becomes empty. It loses its force. The name is still spoken, but Jesus is no longer invoked. The repetition becomes judgment instead of grace. The one who prays must not think he is doing something great. He must see himself as a beggar knocking on the door. As St. Isaac the Syrian says: “This life has been given you for repentance. Do not waste it in vain pursuits.”

The Jesus Prayer thus becomes a mirror. It shows us ourselves. It is not always comforting. It often wounds. But it wounds in order to heal. The aim is not psychological wellness. The aim is salvation—which begins in humility, is sustained by repentance, and is fulfilled in union with Christ.

Practice and Discipline

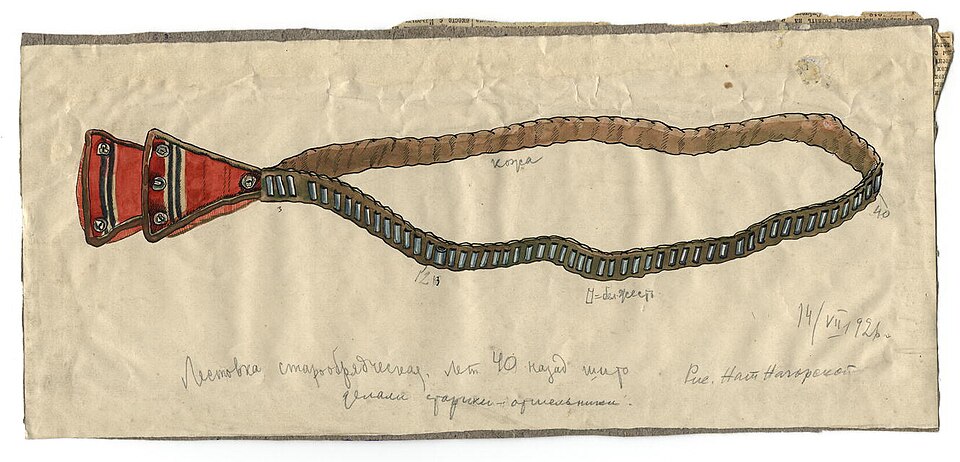

The Jesus Prayer is not a solitary act of private piety. It is embedded within the ascetical and sacramental life of the Church. The use of the lestovka (лестовка) among the Old Believers and the komboskini or prayer rope among other Orthodox Christians is not optional, nor is it symbolic ornamentation. It is a functional tool—a staff for the journey, a sword in battle, and a ladder for the soul.

The Lestovka and Komboskini

The lestovka, literally “ladder,” used by the Russian Old Believers, is a woven strip of leather with a precise number of steps and knots. Each element has meaning—representing the virtues, the wounds of Christ, the Gospels, and more. It is not handmade for decoration; it is a tool of concentration, of discipline, of remembrance.

The komboskini (or chotki), usually made of wool, consists of knots tied with the sign of the Cross, often in groups of 33, 50, 100, or more. It is held in the left hand during prayer, so the right hand is free to make the sign of the Cross. Every knot is a wound upon the pride of the devil. It is not a bracelet. To wear it as an accessory is to profane it. To use it while gossiping, blaspheming, or sinning is worse than not having it at all.

Whichever one you use, the lestovka or komboskini, is for one purpose—to support unceasing prayer and watchfulness. It helps anchor the soul and silence the passions by training the body and mind toward constant recollection of Christ.

Unity of Mind and Heart

The external repetition of the Jesus Prayer is only the beginning. The neptic Fathers—St. Gregory of Sinai, St. Symeon the New Theologian, St. Theophan the Recluse, St. Ignatius Brianchaninov—all teach that the mind must descend into the heart. This is the very foundation of hesychasm.

The mind wanders. The heart sins. When they are separated, man is divided against himself. When they are united, the soul begins to pray with the whole person. This is not achieved by sitting cross-legged and humming with peaceful thoughts. It comes through toil. It comes through vigilance, fasting, silence, tears, confession, and obedience. Without these, there is no true prayer.

Not for the Disobedient

The Jesus Prayer is not for the disobedient, nor for the curious, nor for those who seek experience apart from the Church. There is no such thing as private spirituality in Orthodoxy. To attempt the Prayer without the sacraments is spiritual delusion. To attempt it without confession is pride. To seek visions is to fall into the trap of the demons. We must remember that the demons can imitate light and deceive some Christians. St. Ignatius warns that any form of spiritual practice outside the canonical and ascetical life of the Church is self-willed religion, a mark of prelest—, false holiness, not grace.

The Jesus Prayer is not a path to emotion. It is a path to metanoia—true repentance. The goal is not to feel peaceful, but to become pure. The Ladder of St. John Climacus warns us soberly that the demons rage when we sleep. When prayer becomes real, the battle intensifies.

Linked to the Sacraments

To separate the Jesus Prayer from Confession, Holy Communion, and obedience to a spiritual father is to sever it from its source of power. It is not a stand-alone method. It is a part of the liturgical life, not a replacement for it. The Divine Liturgy, not individual effort, is the centre of the Christian life. The Prayer flows from it and leads back to it. Those who attempt to pursue hesychia without the Church fall into darkness, like monks without a rule, soldiers without an army.

The “peace of Christ,” promised in Philippians 4:7, is not an emotional equilibrium. It is the stillness that comes when the passions are silenced and the nous is illumined. This is the peace that surpasses understanding—not because it is vague or mystical, but because it is divine and therefore beyond what worldly minds can comprehend. It is the peace of the saints. It is the fruit of ascetical suffering joined with sacramental grace.

The Jesus Prayer and Monasticism

This portion touches upon a central pillar of Orthodox theology and spiritual practice: the hesychast tradition, defended by St. Gregory Palamas in the 14th century. The Jesus Prayer is not a technique learned in the classroom, nor is it a pious exercise among many. It is the very breathing of the soul, cultivated most intensely within the furnace of monastic life. Though every Christian may say the Prayer, its mystery is lived most deeply in the silence of the desert, the solitude of the cell, and the stillness of the cloister.

Palamas and the Hesychast Controversy

St. Gregory Palamas stood as the defender of true Orthodox spirituality against the assaults of Barlaam the Calabrian, a Latin-trained intellectual who ridiculed the Athonite monks. Barlaam, infected by scholasticism and rationalism, considered the hesychasts deluded for claiming to experience the uncreated light—the same light revealed on Mount Tabor at the Transfiguration of Christ. He denied the reality of inner prayer and rejected the experiential knowledge of God.

Palamas, a monk of Mount Athos and later Archbishop of Thessaloniki, defended the saints. He proclaimed that God, in His essence, remains utterly unknowable and inaccessible, as all the Fathers affirm. But in His uncreated energies, God reveals Himself and unites Himself to man. These energies are not created effects or symbols. They are God Himself, as He acts. The saints do not see a creature. They see the uncreated light—not by bodily eyes, but by the purified nous. Palamas declared that this union is not philosophical but ascetical—achieved through repentance, purification, and prayer. The Jesus Prayer, in this context, is the primary instrument of that union. It draws the nous into the heart. It cleanses the soul. It fills the man with divine grace. It leads, in rare cases and by God’s will, to the vision of the uncreated light.

The Theology of the Heart

This theology is Orthodox. It is not Latin. It is not rationalist. It does not begin with man analysing God, but with man falling down before God in repentance. It is a theology not of the academy, but of the cave or the desert. Not of the university, but of the monastery. Palamas’ teaching rests on the experience of the saints—from St. Anthony the Great to St. Symeon the New Theologian. It is consistent with the Scriptures: “Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God.” (Matthew 5:8) This “seeing” is not imaginative. It is spiritual perception, made possible through purification.

The intellect cannot attain God. It may speak about Him, but it cannot touch Him. The nous—when freed from passions and joined to the grace of the Holy Spirit—can. And the Jesus Prayer is the central means by which this inner purification occurs.

Monasteries — Fortresses of Prayer

The monasteries are not monuments to the past. They are not cultural institutions. They are not quaint relics. They are fortresses of prayer, bastions of spiritual warfare, and guardians of truth. They preserve the purity of Orthodox prayer because they are built on obedience, silence, and poverty. The monastic cell is a battleground. In that small, confined space, the monk wages war against thoughts, passions, and the demons. The Jesus Prayer is his sword and shield. Every breath becomes prayer. Every movement becomes remembrance. Every tear becomes incense.

While laymen may not live in deserts or cells, they can learn from this. They can carve out time, silence, and stillness. They can fast. They can confess. They can say the Prayer. But they must understand that the Prayer reaches its full depth only when accompanied by the renunciation of self, the struggle against sin, and the discipline of obedience.

The Jesus Prayer is not for the self-satisfied. It is for those who are poor in spirit, those who mourn their sins, those who hunger for righteousness—not in theory, but in the body and the soul. Monastics embody this fully, which is why the depth of the Prayer is best known in their midst.

Warnings and Misuses

The Jesus Prayer is not a technique, not a practice to be taken up like a hobby, nor a spiritual accessory to be worn with a sentimental mood. It is not a breathing exercise. It is not Eastern meditation. It is not a sedative for anxiety. It is prayer to the living God, the crucified and risen Lord Jesus Christ, and it must be uttered with fear and trembling, with faith, and with humility. Anything less is misuse, and misuse of holy things is dangerous.

The Errors of the Modern Mind

In our time, there are many who approach the Jesus Prayer as though it were a mantra or chants of certain false Eastern religions. They repeat it mindlessly, or they use it to attain a state of emotional peace. Some even dare to suggest it as a tool for “mental health” alongside therapy and breathing techniques. This is a profanation of holy things.

The Jesus Prayer is not for mental wellness. It is for genuine repentance. It is not meant to help one “feel better,” but to call down the mercy of God upon a soul weighed down by sin. The saints never spoke of inner calm as an end. They spoke of contrition, mourning for one’s sins, and unceasing prayer. Emotional relief is not a fruit of grace. The fruit of grace is a broken and contrite heart, as David says: “The sacrifice acceptable to God is a broken spirit; a broken and contrite heart, O God, you will not despise.” (Psalm 51:17)

To use the Jesus Prayer apart from this attitude is to call on the Lord’s Name in vain.

The Warnings of the Fathers

The holy Fathers, especially the neptic ones, warn without compromise that the inner prayer should not be pursued without guidance, without obedience, and without a life in the sacraments. The path is narrow. The dangers are many. Chief among them is spiritual delusion. There are those, moved by pride or naïveté, who begin to say the Prayer in large quantities, seeking spiritual experience. Some report seeing light, hearing voices, or experiencing sensations of sweetness or warmth. The Fathers are clear that these are not signs of grace. They could even be traps. The demons can appear as angels. St. Paul wrote that “even Satan disguises himself as an angel of light.” (2 Corinthians 11:14)

St. Symeon the New Theologian, St. Ignatius Brianchaninov, and St. Theophan the Recluse all emphasise that one should not trust spiritual feelings or visions. Trust only repentance. Trust only the sober judgement of a confessor. St. Ignatius warns that even a small movement of pride is enough for God to permit one to fall into delusion, for correction.

The Path of the Humble

True prayer does not exalt. It humbles. The man who truly prays is not filled with light and warmth. He is filled with the knowledge of his own sin. He sees how far he is from God. He says the Jesus Prayer not because it soothes him, but because he cannot live without Christ’s mercy.

St. Isaac the Syrian writes: “This life has been given to you for repentance; do not waste it in vain pursuits.” The Jesus Prayer is given to help us repent. It is not a religious product. It is not a calming phrase. It is a cry of desperation to the Judge of all.

If you do not believe in the person of Jesus Christ, if you do not submit to Him as Lord and God, if you do not confess your sins and strive to change your life, then repeating His Name will do you no good. The demons also speak His Name, but they do not obey Him. Therefore, let no one say the Jesus Prayer as though it were magic. Let no one speak it without fear. Let no one use it as though it were a charm for peaceful feelings. It is the prayer of the publican, not the Pharisee. It is the cry of the blind men, not of the self-assured. It is the rope thrown to the drowning man. To misuse it is to mock the mercy of Christ.

Say it with compunction. Say it with trembling. Say it as a beggar before the throne of God. Only then will it bear fruit. Only then will the demons flee. Only then will the soul begin to be healed.

Conclusion

The Jesus Prayer is not one option among many. It is not a devotion to be picked up when one feels spiritual or put aside when one is tired. It is not a supplement to the Orthodox life. It is the very heart of the Orthodox life. It is the cry of the soul stripped of illusions, laid bare before the Living God. It is the voice of the publican, the cry of the blind men, the tears of the harlot, the plea of the thief on the cross.

“There is salvation in no one else, for there is no other name under heaven given among mortals by which we must be saved.” (Acts 4:12) That Name is not an abstraction. It is not an idea. It is not a theological concept. It is the Name of the God-man Jesus Christ, born of the Virgin, crucified under Pontius Pilate, risen from the dead, ascended in glory, and coming again in dread judgement. When we say the Jesus Prayer, we invoke that Name—not as a sound, not as a formula, but as a Person, present and powerful, whose mercy is our only hope.

The Jesus Prayer is not emotional. It is not to stir the feelings. It is a confession of the truth of who we are and who God is. It does not flatter the soul. It accuses it. It does not lead to spiritual self-satisfaction. It crushes pride. To say, “have mercy on me, a sinner,” is to agree with God’s verdict against sin and to beg for what we do not deserve. This is why the Fathers call it the prayer of the heart. Not because it is warm or poetic, but because it pierces to the deepest part of man’s being. The lips may say it, but the heart must weep it.

It is not optional, because sin is not theoretical. It is a sickness, and we are all infected. It is a fall, and we have all stumbled. It is a fire, and we are all scorched. If we are to be healed, lifted, and cleansed, it must be by Christ. And if by Christ, then we must cry to Him unceasingly.

St. John of Kronstadt said: “Prayer is the breathing of the soul. As the body cannot live without air, so the soul cannot live without prayer.” To abandon the Jesus Prayer is to begin spiritual suffocation. To embrace it is to inhale the mercy of God.

The Apostle commands: “Pray without ceasing.” Again, this is a command to be obeyed. The Church has given us the Jesus Prayer as the means to obey it. The monk says it in the stillness of his cell. The layman says it as he works. The old woman says it as she lights her lamp. The child whispers it as he falls asleep. Every breath should become prayer. Every step, a rhythm of repentance. Every thought, a movement towards the Name. This is how the nous is purified. This is how the passions are quieted. This is how Christ is enthroned in the heart.

“Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner.”

This is not just a sentence. It is the Orthodox Christian’s answer to death, to despair, to temptation, to delusion, to pride, to loneliness, to fear, to every demonic assault. This prayer is fire. It is a sword. It is the ark of salvation on stormy seas. It is the lifeline to Christ. Let no Orthodox Christian despise it. Let none neglect it. Let all say it, slowly, attentively, with tears. Let it be on our lips as we rise, as we lie down, as we labour, as we suffer, and when we die. And let it be our final breath, as the soul departs to meet the Judge: “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner.”

If you wish to live, learn to pray. If you wish to see God, purify your heart. And if you wish to purify your heart, say the Jesus Prayer. Not once. Not twice. Always. Until your soul is nothing but prayer, nothing but longing, nothing but repentance. Only then will you understand why the saints called the Jesus Prayer the prayer of the heart.

May God bless you +

Fr. Charles

14 August 2016

Comments are closed.