Living with hope is at the heart of the Christian life as the Church understands it. In our tradition, hope is a theological virtue given by God and received in freedom, binding the soul to the promises already inaugurated in Christ and yet to be fully revealed in the age to come. It is inseparable from faith and love, and it matures within the life of the Church as we are led towards theosis—the healing and elevation of the human person by grace. St. Paul teaches, “We are saved by hope. But hope that is seen is not hope. For what a man seeth, why doth he hope for?” (Romans 8:24). This saving hope fixes the heart on Christ’s Resurrection and Ascension, on His promised appearing in glory, and on the inheritance of incorruption. The Orthodox mind therefore treats hope not as an inward mood but as a steady participation in the divine life, a stance of filial trust fostered by the Holy Spirit, an “anchor of the soul” that holds fast amidst the tides of time (cf. Hebrews 6:19).

The life of hope does not cancel suffering; rather, grace grants suffering a paschal meaning. In the Church we learn to carry the Cross in union with Christ, confident that His victory is already active in the midst of trial. St. Peter exhorts the Church, “Be you therefore also ready: because at what hour you know not the Son of man will come” (Luke 12:40). Watchfulness and prayer keep the heart awake to this coming, so that afflictions are neither denied nor allowed to define our destiny. Fasting, vigils, and the sober joy of Great Lent teach this “bright sadness,” in which penitence and hope interlace without contradiction. Thus Christians are trained to read adversity through the lens of Pascha, trusting that “the sufferings of this time are not worthy to be compared with the glory to come, that shall be revealed in us” (Romans 8:18). The martyrs, confessors, ascetics, and the sick who endure with patience bear witness that hope does not evaporate in the furnace; it is tempered there.

Because hope is ecclesial, it takes concrete form in the Mysteries and in the daily ascetical life. In Baptism and Chrismation the believer is sealed with the Spirit who cries “Abba, Father,” and hope begins to breathe with filial confidence. In the Holy Eucharist the Church receives the pledge of the age to come, being nourished by the very Body and Blood of the risen Lord. Confession restores the downcast, teaching the soul to expect mercy where pride had expected judgement. The anointing of the sick steadies the fearful with the consolation of the Comforter. From these springs of grace flows a manner of life marked by sobriety, gentleness, courage, and thanksgiving. Hope also shapes the unseen warfare of the heart. The Jesus Prayer purifies wandering thoughts; alms-giving breaks the tyranny of fear by entrusting our future to God; forgiveness loosens the knots of resentment and clears room for divine consolation. St. John wrote, “And every one that hath this hope in him, sanctifieth himself, as he also is holy” (1 John 3:3). This is not moral uplift but transfiguration: ordinary tasks become offerings, speech becomes blessing, and time becomes expectation.

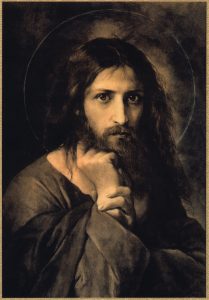

Our hope is also deeply communal. We are saved as members of a Body, supported by the prayers of the saints and by one another’s intercessions. Parish life—its common prayer, its shared burdens, its works of mercy—forms a school of hope in which the strong carry the weak and the weak teach the strong to depend on God. Writing to the Thessalonians, St. Paul instructed, “Comfort one another; and edify one another, as you also do” (1 Thessalonians 5:11). The remembrance of the departed at the Divine Liturgy, the memorial services, and the cry “Memory eternal” all confess that love is stronger than death and that we await the resurrection of the body. The veneration of icons, too, is a quiet proclamation of hope—by honouring the saints whom God has glorified, we confess the destiny of human nature in Christ and the promise that the same holiness can be fashioned in us.

Vigilance remains essential, for hope is sustained by watchfulness and obedience. Christ’s words about His coming do not incite anxiety; they purify desire, directing it towards a kingdom that cannot be shaken. Our tradition speaks of synergy—our cooperative labour with divine grace—by which hope is guarded and enlarged. We keep a prayer rule, examine our conscience, receive the Mysteries, and cultivate humility, not to earn divine favour but to keep the heart open to the presence already given. The Mother of God, “Joy of all who sorrow,” and the choir of saints surround this labour with their prayers, so that none strives alone. In all of this the Church bears witness that Christian hope is not wishfulness. It is the steadfast confidence, born of the Resurrection, that the Lord will complete what He has begun in us. To live with such hope is to radiate quiet courage, to steady others when they falter, and to anticipate with reverence the day when faith gives way to sight and love abides without end—“hope confoundeth not; because the charity of God is poured forth in our hearts, by the Holy Ghost, who is given to us” (Romans 5:5).

May God bless you +

Fr. Charles

29 August 2025

Comments are closed.