Question: Is Tobit, Judith, additions to Esther and Daniel, 1 and 2 Maccabees, Wisdom of Solomon, Sirach, Baruch, Prayer of Manasseh and Josephus’ Wars of the Jews part of the Orthodox canon? Were they part of the Jewish Bible? And someone told me these books were never in the King James Bible. Is there any real reason to read these books?

Question: Is Tobit, Judith, additions to Esther and Daniel, 1 and 2 Maccabees, Wisdom of Solomon, Sirach, Baruch, Prayer of Manasseh and Josephus’ Wars of the Jews part of the Orthodox canon? Were they part of the Jewish Bible? And someone told me these books were never in the King James Bible. Is there any real reason to read these books?

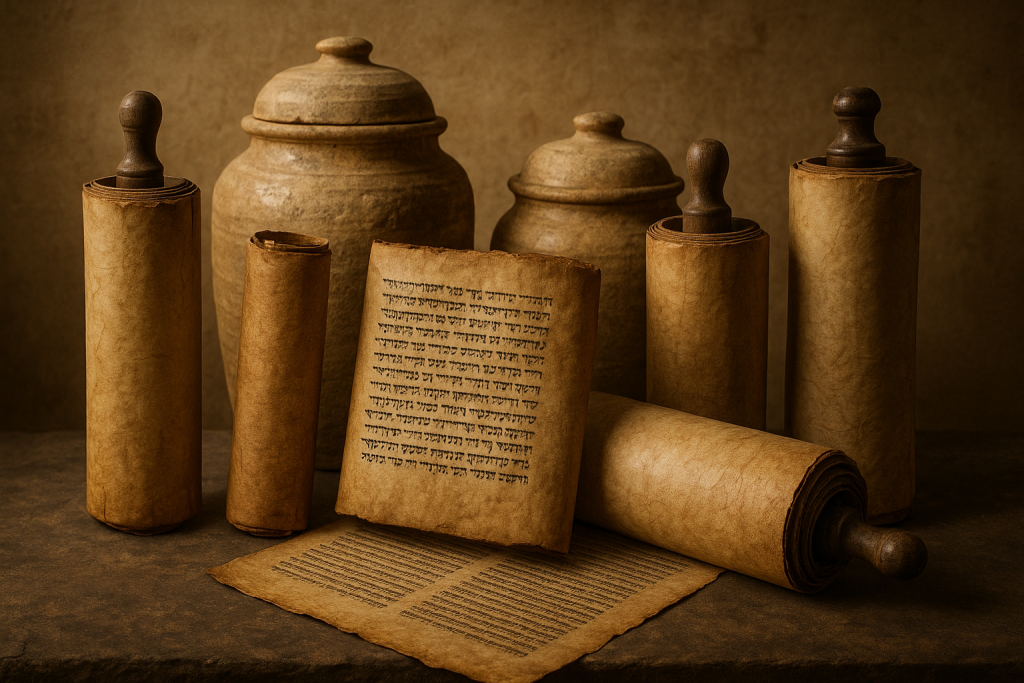

The books you listed—Tobit, Judith, the additions to Esther and Daniel, 1 and 2 Maccabees, Wisdom of Solomon, Sirach (Ecclesiasticus), Baruch, and the Prayer of Manasseh—are part of what is often termed the “Deuterocanonical corpus” in the Roman tradition and are accepted as fully canonical in the Orthodox Churches. Their presence in both the Septuagint (LXX) and the Aramaic/Syriac Peshitta is indeed historically significant and speaks to their wide early use among Jews and Christians alike. I will come back to your mention of Wars of the Jews momentarily.

The Septuagint, translated in stages beginning in the 3rd century B.C. in Alexandria, was the primary scriptural text for Greek-speaking Jews and the earliest Christians. It includes numerous texts not found in the later Masoretic Hebrew canon, including:

Tobit, Judith, Additions to Esther (including the prayers and visions), Wisdom of Solomon, Sirach (Ecclesiasticus), Baruch and the Letter of Jeremiah, Additions to Daniel (Prayer of Azariah, Song of the Three Holy Children, Susanna, and Bel and the Dragon), 1–4 Maccabees (with 1–2 being the most prominent liturgically and theologically)

These books were in common circulation among Hellenistic Jews, and many had been written in Greek or translated from Semitic originals.

Importantly, the majority of Old Testament citations in the New Testament are drawn from the LXX, not the Masoretic text. This alone reflects the early Christian esteem for the Greek Scriptures, including these books.

The Peshitta, the authoritative Aramaic/Syriac version of the Bible, also preserves many of these texts. In early editions of the Peshitta Old Testament, one finds: Tobit, Judith, Wisdom, Sirach, Baruch, Prayer of Manasseh, 1–2 Maccabees

In addition, as you mentioned in your question, there are copies of the Wars of the Jews by Josephus preserved in Aramaic and used by some Eastern communities.

It is incorrect to think of a single, uniform “Jewish Bible” prior to the finalisation of the Tiberian Masoretic Text tradition in the 9th–10th centuries A.D. Rather, there were plural Jewish canons, reflecting the linguistic, cultural, and geographic diversity of Jewish communities. Greek-speaking Jews in Alexandria, Aramaic-speaking Jews in Syria and Mesopotamia, and Hebrew-speaking Jews in Judea and Galilee often had overlapping but not identical textual traditions.

The early Christian Church, composed initially of Greek-speaking Jews, Aramaic-speaking Jews, and Gentile converts, inherited the Scriptures in use in their respective communities. The use of the LXX and Peshitta by early Christians is thus not accidental, but a direct extension of the diverse Judaism from which early Christianity emerged.

The Fathers of the Church, including Athanasius, Augustine, Clement of Alexandria, and others, frequently cite from the Deuterocanonical books. These texts were read liturgically, quoted as Scripture, and used theologically, especially: Wisdom and Sirach (for their moral and doctrinal instruction); Maccabees (for teachings on martyrdom and resurrection); Tobit and Judith (for their typological significance); and Baruch (as part of the Jeremiah tradition).

This demonstrates that their reception was not a later imposition, but part of the Church’s early scriptural life.

The rejection of these books by some later Rabbinic authorities—particularly those associated with the school of Yavneh (Jamnia) in the late 1st century—did not affect the Christian canon, which had already been shaped in a broader context.

The Reformers’ rejection of the Deuterocanon was largely based on their preference for the Masoretic Hebrew canon (a much later text than the original Old Testament), whereas the Orthodox Church, faithful to the broader tradition of the early Church, retained these original biblical writings.

The claim that the so-called “Apocryphal” books were never part of the King James Version (KJV) or earlier English Bibles is demonstrably false and historically uninformed. These books were not only included in the original 1611 KJV, but also in earlier translations such as John Wycliffe’s Bible (1382–1395), Coverdale’s Bible (1535), and the Great Bible (1539), the Reformed Geneva Bible (1560), and the Douay-Rheims Catholic Bible (1582-1610).

The original 1611 edition of the KJV most certainly contained the following books and portions now labelled “Apocrypha”, placed between the Old and New Testaments: 1 Esdras, 2 Esdras, Tobit, Judith, additions to Esther, Wisdom of Solomon, Ecclesiasticus (Sirach), Baruch (including the Letter of Jeremiah), Song of the Three Holy Children, Story of Susanna, Bel and the Dragon, Prayer of Manasseh, 1 Maccabees, 2 Maccabees.

These were integral parts of the 1611 printing, found in all complete editions printed by royal license until well into the 17th century.

The removal of these books from many Protestant Bibles did not occur until the 19th century, and primarily due to the influence of rising anti-Catholic sentiment, especially in the English-speaking world. Some Protestant sects viewed these biblical books as being “too Catholic.” Orthodoxy has always retained these books as canonical, especially since they were part of the original biblical text before the early Church existed. The Anglican Communion historically retained them for liturgical use, and many Lectionaries continue to assign readings from them. Martin Luther, the founder of Protestantism, included them in his German Bible (1534), placing them between the Old and New Testaments, and described them as “books which are not held equal to the Scriptures but are useful and good to read.” Their exclusion from modern Protestant Bibles is a relatively late development driven more by ideology and probably economics than by fidelity to early Christianity.

Many Protestants simply do not know the full historical development of the canon, having been taught that the Bible has always included 66 books and that the others were “added by the Catholics.” The Deuterocanonical books were not added by the Catholic Church at the Council of Trent, but had been used for centuries by Jews and Christians alike. Trent merely reaffirmed what had long been received in the Western Church. These books were read and honoured by Greek-speaking Jews, who lived in Alexandria, Asia Minor, and other parts of the diaspora. They were also found in ancient Aramaic and Syriac traditions, such as in the Peshitta. Thus, they were accepted by many Jews well before the rise of Christianity. The Councils of Hippo (393) and Carthage (397, 419)—which fixed the New Testament canon—also included the Deuterocanonical books in the Old Testament list. The exclusion of these books is a relatively modern phenomenon, not the historical norm. For centuries, the Church of England, Lutherans, and other Protestants included these books, even if not all held them to be fully canonical. The spiritual depth and Christological foreshadowing in these books often speak for themselves.

The canon of Scripture is not self-evident—it is a received tradition. If we trust the Church to preserve the New Testament, why would we not trust it in preserving the Old? Let us seek truth together, guided by prayer and humility.

Why should Christians read the Deuterocanonical books?

The Deuterocanonical books are of considerable importance to the ancient Christian faith, both historically and spiritually. Though often misunderstood or neglected in most modern Protestant sects, these books have been a vital part of the Church’s scriptural and liturgical life for over two millennia. Their continued reading and reverence is not simply a matter of tradition—it is a matter of spiritual edification, doctrinal integrity, and historical fidelity. To neglect these books is to detach oneself from the scriptural inheritance of the early Church.

These books are critical for understanding the intertestamental period, the centuries between the end of the Old Testament (as structured in Protestant Bibles) and the coming of Christ.

For example, 1 and 2 Maccabees provide essential history of the Jewish struggle against Hellenistic oppression, the rededication of the Temple (celebrated at Chanukah ), and the martyrdom of the faithful—a clear anticipation of Christian martyrdom. Baruch and the Letter of Jeremiah help explain the experience of exile and the theological reflection on idolatry. The Wisdom of Solomon addresses themes of divine justice, resurrection, and the role of Wisdom—highly important for Christological typology. Sirach (Ecclesiasticus) offers an immensely rich collection of ethical teaching, similar to Proverbs but with deeper reflection on creation, free will, and the law. Without these texts, the continuity between the Old and New Testaments appears fractured.

Many doctrines and themes found in the New Testament have strong precedents in the Deuterocanon.

For example, the resurrection of the dead and prayers for the departed (2 Maccabees 12:43–46) anticipate both the early Church’s doctrine of eternal life and intercessory prayer. The sevenfold Holy Spirit (Wisdom 7:22–23) corresponds to Isaiah 11:2–3 and Revelation 1:4, forming part of the traditional Christian teaching on the Holy Spirit’s gifts. Faith and righteousness (Wisdom 5, Sirach 15) and the concept of grace in Wisdom and Baruch prepare the way for Pauline theology. The dignity of marriage and the value of alms-giving, fasting, and prayer (Tobit 12:8–10) echo the moral teachings of Christ in the Gospels. These books do not contradict the Gospel—they illuminate it.

These books deepen the Christian spiritual life. They are not dry historical appendices. Instead, they are filled with prayers (e.g., the Prayer of Azariah, the Prayer of Manasseh); hymns of praise (e.g., the Song of the Three Holy Children); reflections on suffering, divine providence, and wisdom.

They have long been used in Christian liturgy, especially in Orthodox and Catholic Churches, and even in the Anglican tradition (via the Book of Common Prayer and the lectionary). They provide language and imagery that deepen Christian prayer, reflection, and understanding.

Many Protestants today reject the Deuterocanonical books on the basis that they are not part of the Hebrew Masoretic Text or that they were “added later” by the Catholic Church. As mentioned above, such thoughts are historically incorrect.

The Deuterocanon was already part of the Greek Septuagint and Syriac Peshitta, which the Apostles themselves used. The New Testament authors cite or allude to the Deuterocanon multiple times. For example, Hebrews 11:35 alludes to 2 Maccabees 7; Romans 1:20–32 reflects the thought of Wisdom of Solomon 13–14; James 1:19 parallels Sirach 5:11.

The exclusion of these books from many Protestant Bibles did not occur until the 19th century, mainly for doctrinal and financial reasons, not because of new historical evidence. Their universal reception across Christendom—except among some branches of modern Evangelicalism—is notable and instructive.

All Christians should read the Deuterocanonical books because they are part of the scriptural heritage of the early Church; theologically rich and spiritually edifying; essential for understanding the full biblical narrative; used liturgically and doctrinally for centuries; confirmed by apostolic usage and Church Fathers; and endorsed by multiple ecumenical councils.

To neglect them is to lose access to a significant part of the Holy Tradition. To rediscover them is to reconnect with the faith of the earliest Christians, who saw in them the voice of God and the preparation for Christ.

Comments are closed.