The veneration of icons is not an option in Orthodox Christianity. It is essential. It is not a cultural embellishment or devotional tool for the simple-minded, but an active and visible confession of the Incarnation of our Lord Jesus Christ. Icons are not tolerated—they are required. Those who oppose icons do not merely misunderstand Orthodox worship; they misunderstand the very Gospel itself.

The Incarnation is the Theological Foundation of Iconography

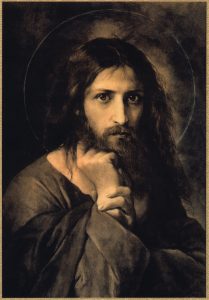

The centre of the Christian faith is not an idea, not a principle, not a philosophy, but a Person: the Incarnate Word of God. “And the Word became flesh and lived among us.” (John 1:14) This verse is not symbolic. It is literal. It declares that the eternal Son of God, who is consubstantial with the Father, took on human nature—entire and uncorrupted—and entered into His own creation. He was not content to speak through prophets, visions, or dreams. He came in person. The eternal Logos, through whom all things were made, became visible. God, who “dwells in unapproachable light, whom no one has ever seen or can see” (1 Tim. 6:16), chose to make Himself known in the face of Jesus Christ. “No one has ever seen God. It is God the only Son, who is close to the Father’s heart, who has made him known.” (John 1:18) This is the theological ground upon which all Orthodox iconography stands. The invisible God has become visible—not as an apparition or symbol, but as a man.

In Christ, divinity and humanity are united “without confusion, without change, without division, without separation,” as the Chalcedonian definition rightly confesses. This union is not temporary. It did not cease with the Ascension. He did not discard His humanity like a garment. The glorified body of the Lord, bearing the marks of the nails and the wound in His side, remains the body in which He sits at the right hand of the Father. This is why icons are not optional. They are not illustrations—they are confessions of the dogma of the Incarnation.

To reject icons is to reject the visibility of God. It is to say that the body of Christ is of no consequence. It is to separate the humanity from the divinity, and by doing so, fall into the pit of ancient heresies. A Christianity without icons is not apostolic. It is not Orthodox. It is a denial of what the Church has always believed—that the eternal Son became man for our salvation and that His very image is worthy of veneration because His humanity is united with His divinity. The Apostle John writes with deliberate clarity: “We declare to you what was from the beginning, what we have heard, what we have seen with our eyes, what we have looked at and touched with our hands.” (1 John 1:1) Christianity is not based on imagination. It is not a spiritual philosophy detached from historical events. The Apostles saw the Lord with their own eyes. They touched Him. They ate with Him. They witnessed His suffering, death, and bodily resurrection. Their preaching is not conjecture. It is testimony.

Likewise, the Apostle St. Peter rebukes any attempt to spiritualise the Gospel into myth or allegory: “For we did not follow cleverly devised myths when we made known to you the power and coming of our Lord Jesus Christ, but we had been eyewitnesses of his majesty.” (2 Peter 1:16) The icon is a visual extension of that apostolic witness. It proclaims, not through words but through sight, that the Lord was seen and is still seen by faith through the holy images preserved in His Church. If Christ truly became man, then His appearance matters. His human face matters. His gestures, His posture, the look of His eyes—all these are not incidental. They belong to His real humanity. The Orthodox Church, in depicting Him, does not claim to capture His essence, which is impossible. It does, however, declare that since He was visible, He may be depicted. If He was truly incarnate, then the commandment against graven images is fulfilled, not violated, when His image is written in sacred iconography.

To say that images have no place in Christian worship is to say that Christ’s body is irrelevant. It is to say that God’s entry into human history in the flesh has no bearing on the life of the Church. This is blasphemy, not piety. It is an attempt to erase the Gospel under the guise of reverence. The icon does not distract from Christ—it confesses Christ. It affirms that our God is not a distant abstraction, but Emmanuel, God with us, in the flesh.

The Orthodox icon is not only a simple reminder; it is a bold declaration. It is not subjective. It is objective. It stands as a visible testimony to the truth of the Gospel—that the eternal God has become man, and that He may be seen, honoured, depicted, and venerated—not in His divine essence, but in the flesh He assumed for our salvation.

The False Argument of Iconoclasm

Iconoclasts—both ancient and modern—have long sought to justify their error by citing the Second Commandment: “You shall not make for yourself an idol” (Ex. 20:4). They seize this verse and wrench it out of its context, wielding it like a weapon against the Apostolic Tradition. They fail to read the Scriptures as the Church has always read them. They take what was a prohibition against pagan idolatry and distort it into a blanket rejection of all visual representation. This is not reverence. It is blindness.

The commandment continues: “You shall not bow down to them or worship them.” (Ex. 20:5) This clarifies the point. The sin condemned is not the existence of images but the worship of them as gods. The ancient pagan nations surrounded Israel with carved deities to whom they offered sacrifice. They bowed before statues believing them to embody the divine. This is the abomination that God condemned—not the mere existence of visual form. If one cannot distinguish between idolatry and veneration, then one has not understood either the Bible or the nature of God’s revelation to Israel.

If we are to follow the iconoclast logic to its conclusion, then God stands guilty of commanding what He Himself forbade. For He instructed Moses in precise terms to fashion two cherubim of gold: “You shall make two cherubim of gold; you shall make them of hammered work, at the two ends of the mercy seat.” (Ex. 25:18) These were not decorations for private use. They were part of the liturgical centre of Israel’s worship—the Holy of Holies. Their wings stretched over the Ark of the Covenant, from where God would speak. These were images. Sacred, visible, material images—commanded by God Himself.

Again, in Numbers 21:8–9, when the people of Israel were afflicted by venomous serpents, the Lord did not provide healing through an abstract idea. He commanded Moses to construct a bronze serpent and lift it high upon a pole. “And whenever a serpent bit someone, that person would look at the serpent of bronze and live.” (Num. 21:9) This was not magic. It was not superstition. It was divine commandment. God chose to work through the gaze upon a physical object as a means of His mercy. This is what the icon is in the Church—not an idol, but a visible vessel of divine action. This same bronze serpent was later destroyed by King Hezekiah because it had become an object of idolatry (2 Kings 18:4). Notice what this means: the image itself was not the problem. The problem was that the people burned incense to it and called it “Nehushtan.” It had become divorced from its original purpose and had become an object of worship. Hezekiah did not forbid all images. He destroyed one that had become an idol. The principle remains unchanged—it is not the image that is evil—it is the heart of man that makes it so.

If God were utterly opposed to all material representations, then His own commandments would contradict each other. He who forbade idolatry also commanded sacred art. He who declared Himself invisible revealed Himself in visible ways. He descended in the cloud, He appeared in fire, He inscribed His law on tablets of stone with His own finger. And ultimately, He revealed Himself in the flesh in the Person of Jesus Christ. How then can we say that all images are forbidden? Only those blind to the Incarnation can make such a hideous, unbiblical claim.

The rejection of icons is far from being a biblical stance. It is not a patristic stance. It is a modern invention, a resurgence of the iconoclastic heresy that tore the Church in the eighth and ninth centuries. That heresy, rooted in a false piety, was condemned at the Seventh Ecumenical Council in 787. The Fathers, gathering in Nicaea under the guidance of the Holy Spirit, declared unequivocally that the veneration of icons is part of the Orthodox faith. The honour given to the image passes to the prototype. Those who honour the icon honour Christ, His Mother, and His saints. Those who destroy icons rebel against Christ’s Church and His Gospel. Let us not be deceived by those who wrap their heresy under the cover of a Bible. The devil himself quoted the Psalms when tempting Christ. Quoting the Bible without the Church leads to error. The Holy Scriptures are not self-interpreting. They belong to the Church that preserved them, read them, and canonised them. And that same Church has always had icons.

The rejection of icons is not a mark of faithfulness. It is a sign of separation from the Apostolic Tradition. It is a rupture with the Church of the Fathers. It is a mutilation of Christian worship. The iconoclasts of old were rebuked, excommunicated, and anathematised for their error. Their modern counterparts deserve no less. Their ideas are foreign to the Church, and they remain foreign.

Icons as Theology in Colour

The Orthodox icon is not religious art. It is not spiritual decoration. It is theology. It is doctrine rendered in line, form, and colour. The icon is not the product of artistic fancy or subjective inspiration. It is written—not painted—because it speaks with the same authority as the Church’s hymnography and liturgical texts. It is not a silent object; it is a proclamation of the truth. It is Scripture made visible, and its legitimacy comes not from the taste of the artist, but from its faithfulness to the Tradition handed down from the Apostles.

St. John of Damascus, writing against the iconoclasts, said clearly: “I do not worship matter. I worship the God of matter, who became matter for my sake and deigned to dwell in matter and through matter worked my salvation.” The icon confesses this reality. It proclaims, without apology, that matter has been sanctified through the Incarnation. Christ did not take on flesh to discard it. He glorified it. Therefore, to depict His flesh is not to belittle Him—it is to confess Him.

Icons are not emotional aids. They are not for sentiment or mood. They teach. They instruct. They catechise. Every detail in an icon is deliberate and theological. The elongated figures, the inverse perspective, the solemnity of expression, the stylised features—these are not mistakes. They are intentional rejections of naturalism. The icon is not a photograph. It does not try to recreate the flesh according to fallen sight. It reveals the transfigured flesh of the age to come.

The icon’s background of gold is not an artistic embellishment. It is a confession that the person depicted stands in the uncreated light of God. The lack of shadows in an icon is not an error—it reflects the theological truth that there is “no shadow of turning” in the Kingdom of Heaven (James 1:17). The stylised features, the disproportionate hands, the stillness of posture—these all serve to remove the icon from the temporal and place it in the realm of eternity. The icon is a window into heaven. It is not meant to look like this world, because it is not of this world.

An icon of Christ is not a guess at His appearance. It is a continuation of the living memory of the Church, passed down from those who saw Him. St. Luke the Evangelist, according to ancient tradition, was the first iconographer of the Theotokos. He did not invent her features. He recorded them. The Church has preserved that tradition. To look upon her icon is to see the face known and loved by the Apostles. This is not sentiment—it is continuity.

Similarly, icons of the saints testify that those who are in Christ are alive, not dead. As our Lord said: “He is God not of the dead, but of the living, for to him all of them are alive.” (Luke 20:38) When we venerate an icon of a saint, we are not honouring a relic of the past. We are honouring one who now stands in glory before God. The icon reminds us that the Church is not bound by time. The Church Triumphant is present with us, and the icon is a visible witness to that communion.

To those who say that the icon distracts from Christ, we answer that the icon reveals Christ. The Gospel is not only heard—it is also seen. Just as the Word became flesh, so too the Gospel takes on visible form in the icon. It teaches those who cannot read. It edifies those who come in prayer. It speaks when words fail. It stands silently, but its message is unrelenting. The icon says: God is with us.

The Seventh Ecumenical Council declared that the icon is not a neutral object. It is a bearer of grace. The honour shown to the icon passes to its prototype. “He who venerates the icon,” say the Fathers, “venerates the person depicted.” This is not superstition. It is Christology. The icon is not magic. It is ecclesial. It belongs to the Church, and only within the Church can it be rightly understood. The rejection of icons is not only a rejection of art—it is a rejection of doctrine. It is an attack on the very nature of the Incarnation. It is a war against the senses. It is Gnosticism reborn, dressed in the garments of false piety. Those who seek to purify the Church of icons have already lost the Church. For the Church without icons is a Church without Christ in the flesh.

To tear down icons is to tear pages from the Gospel. To banish them from the temple is to declare that the God who became man cannot be depicted. This is heresy. This is blasphemy. And it must be denounced without hesitation. The icon belongs to the life of the Church as much as the Gospel itself, for both declare the same mystery: The Word became flesh and lived among us, and we have seen His glory. (John 1:14)

Veneration is Not Worship

Honouring the Saints Without Idolatry

There is no confusion in the mind of the Church between veneration (proskynesis) and worship (latreia). The former is honour, the latter is adoration. To conflate the two is to commit a category error, both theological and linguistic. The Orthodox Church venerates icons. It worships only God. Any accusation beyond this is either ignorance or malice. We are not idolaters, and we do not pretend to be.

Veneration is an ancient and biblical practice. The commandment to “Honour your father and your mother” (Exodus 20:12) is not a command to worship them. It is a command to give due respect and reverence. St. Peter wrote: “Honour everyone. Love the family of believers. Fear God. Honour the king.” (1 Peter 2:17) If we are commanded to honour those in earthly authority, are we then forbidden to honour those who reign with Christ? If we do not even worship the king, yet we are commanded to honour him, shall we not honour the saints, who shine with the light of divine grace, not by nature but by participation? The saints are not equal to God. We do not adore them. But they are friends of God. They are His servants, and they reign with Him. “If we endure, we will also reign with him.” (2 Tim. 2:12) Shall we not honour the soldiers of the heavenly King? The Book of Revelation declares that the saints “follow the Lamb wherever he goes” and that their “deeds follow them.” (Rev. 14:4, 13) To honour them is to honour Christ, whose grace has made them what they are.

This veneration is not abstract. It is concrete. Throughout the Scriptures, grace is often communicated through material means. The bones of Elisha revived a corpse. (2 Kings 13:21) His body had no power on its own, yet it became the means of God’s healing touch. In the New Testament, St. Peter’s shadow healed the sick (Acts 5:15), not because shadows have inherent power, but because the Spirit of God rested upon him. Handkerchiefs that had touched the Apostle Paul were carried to the sick, and they were healed, and evil spirits fled. (Acts 19:12) This is not pagan superstition. This is the biblical witness. These objects were not worshipped, but they were rightly honoured, because God had chosen to act through them.

Icons, like relics, are material vessels through which grace is manifested. They are not gods. They are not sources of divine power. But God, who created matter, uses matter for the sake of salvation. To venerate an icon is to confess that the Incarnation has not been undone—that the Word truly became flesh, and that His saints, having been united to Him, may be depicted and honoured. We do not honour the plank or the pigment. We honour the holy one depicted. This is the teaching of the Church.

The Seventh Ecumenical Council in 787, meeting in Nicaea under the authority of the Catholic Church—meaning the Orthodox Church in its fulness, not the innovating Roman sect of later centuries—settled this question definitively. The Council declared: “The honour paid to the image passes to the prototype. He who venerates the image, venerates the person depicted in it.” This decree is not optional. It is not open to private interpretation. It is not simply a pious opinion. It is dogma. It is the infallible ruling of the universal Church, guided by the Holy Spirit. To reject this is to fall into heresy. The iconoclasts were condemned, not for a lack of artistic taste, but for their doctrinal error. They denied the visibility of the Incarnate God and the glorification of the human body in Christ. Their denial of icons was, at its root, a denial of Christ’s real humanity. They were condemned by bishops, martyrs, and confessors—by the entire Orthodox Church.

We must be clear—icon veneration is not some optional tradition, tacked on to Christianity for cultural enrichment. It is bound up with the very confession of the faith. It is Christological at its core. If Christ cannot be depicted, then He has not truly come in the flesh. If the saints cannot be honoured, then grace is not real. If matter cannot mediate blessing, then sacraments are illusions. This is why the Church stood firm at Nicaea, and this is why the Triumph of Orthodoxy is celebrated every year on the first Sunday of Great Lent—not as nostalgia, but as dogmatic necessity. Those who accuse us of idolatry do not understand what we do, and they certainly do not understand the Incarnation. If they worship nothing they can see, hear, touch, or depict, then they have embraced the Gnostic heresy. They have fled from the Word made flesh and returned to the shadows. We shall not follow them into that darkness. We stand with the Fathers. We stand with the Councils. We stand with Christ and His saints.

The icon is a confession. It declares that the saints are alive. It proclaims that the human body, once deified by grace, may be depicted and honoured—not adored, but honoured. The early Church would not have permitted its use had it believed it to be a stumbling-block to salvation. On the contrary, it canonised the practice. It gave it dogmatic status. We obey.

To venerate an icon is to bow before the God who is glorified in His saints. To kiss the icon of the Theotokos is to affirm her unique place in salvation history. To honour the martyrs is to recognise the triumph of Christ in their suffering. And to do so with reverence and clarity is to stand within the one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church. Anything less is deviation.

The Testimony of the Church Fathers

The early Church was not iconoclastic. The catacombs are filled with sacred images—of Christ, the Theotokos, and the saints. The Church never banned icons. That idea arises from heresy, especially the influence of Islam and certain Jewish converts who rejected the Incarnation.

Saint Basil the Great wrote: “The honour shown to the image passes to the prototype. He who venerates the image venerates the person represented in it.”

Saint John Chrysostom said that when we see the image of a saint, we should permit it to stir up in ourselves the desire to imitate his virtue.

These are not late additions. These are men of the fourth century. They belong to the undivided Church.

The Icon in the Life of the Church

Icons are not optional. They are not decorations. They are not private ornaments for the pious. They belong to the very life and identity of the Orthodox Church. Their presence in the temple, in the home, and in the heart of the believer is not a luxury but a necessity. Icons are instruments of prayer, windows into the kingdom of God, and concrete affirmations of dogma. To remove them is not to simplify the faith—it is to mutilate it.

To walk into an Orthodox church is not to enter a neutral space. It is to step into sacred ground. One is no longer in the world, though still in the body. One is in the antechamber of the age to come. The architecture itself is theological. The dome above reveals Christ Pantocrator, not as an idea but as a sovereign Lord. The apse holds the Theotokos—not as a quaint figure, but as our Blessed Mother bearing the Incarnate God in her arms. The iconostasis stands not as a blockade, but as a testament. It does not hinder—it declares. It reveals that worship is not a social gathering, but a divine mystery offered in order, with reverence, according to the tradition received—not invented.

Every icon on the walls of the temple preaches a sermon. These walls are not silent. They proclaim the Gospel visually, bodily, and directly. The icon of the Nativity declares the humility of God. The icon of the Crucifixion declares His love unto death. The icon of the Resurrection proclaims that death is trampled and Hades is spoiled. And the faces of the saints look not down upon us, but into us, bearing witness to what we are called to become—men and women transfigured by grace, conformed to Christ, and radiant with the uncreated light.

The Church is not a hall for lectures. It is not a meeting place for like-minded spiritual consumers. It is the Body of Christ, militant on earth, triumphant in heaven. The icon testifies to this unity. When we gather for the Divine Liturgy, we do not gather alone. The angels join us. The saints surround us. The Theotokos intercedes. The Lord stands in our midst. This is not rhetoric—it is reality. “But you have come to Mount Zion and to the city of the living God, the heavenly Jerusalem, and to innumerable angels in festal gathering… and to the spirits of the righteous made perfect.” (Heb. 12:22–23) This is not poetry. It is liturgical fact. The icon makes it visible.

The iconostasis—the icon-bearing screen between the nave and the sanctuary—is not an obstacle. It is a theological boundary. It declares that God is holy and that worship must be ordered, not casual. It shows that the priest does not act on his own authority, but stands in the place of Christ, doing only what has been entrusted to him. It reflects the hierarchy of heaven, not the egalitarianism of the dark, fallen world. The saints depicted there—John the Baptist, the Theotokos, the patron saint, the local bishop, the angels—are not there as decoration. They are there to receive our prayers and to bring them before the throne of God. They are present. They are alive. The icon affirms it. Neither are the saints in the icons imaginary. They are not idealised types. They are men and women who lived, struggled, fasted, wept, bled, and died in the flesh. Their images are not photographs, but spiritual likenesses. They are not naturalistic—they are liturgical. Their eyes are enlarged, for they see clearly. Their mouths are small, for they speak little. Their faces are calm, for the passions have been subdued. Their gestures bless, their posture prays, their very garments preach. Every line in an icon is theological. Every colour has purpose. There is no artistic licence in the icon. There is only obedience to the canon of holy form.

Icons are didactic. They teach without words. In an age where literacy was rare, the icon was the Gospel. Today, though the faithful can read, they have forgotten how to see. The icon trains the eye to behold holiness. It disciplines the gaze. It raises the vision of the soul. It rebukes the impure imagination. It calls the mind away from vanity and the senses away from corruption. It is an ascetical presence. One does not glance at an icon as one glances at a painting. One stands before it. One prays before it. One fasts before it. One weeps before it. And if the soul is awake, one is changed by it.

Icons also testify to the stability and unity of the Orthodox Church. The iconographic tradition has remained unbroken. Though empires have fallen and heresies have arisen, though schisms have torn away whole regions, the icon has remained intact. From Sinai to Athos, from Cappadocia to Kiev, from Antioch to Alaska, the same Christ is depicted, the same Theotokos, the same saints, in the same form, with the same theology. No Protestant denomination can make this claim. Most of their churches are whitewashed and empty, or else filled with secular art. The same can be said about the post-Vatican II Roman Catholic Church. Their theology has fragmented, and their gaze has been turned inward. The Orthodox Church, by contrast, continues to proclaim the Incarnation in every icon. It continues to teach the faith not only by tongue, but by sight. It has not moved with the world. It has stood where it always has.

Let us be clear. The icon is not for the museum. It is not for casual observation. It is not art. It is sacred. It belongs in the temple, in the home, in the heart. A house without icons is a house without blessing. A church without icons is a tomb. A theology without icons is a gnostic aberration, alien to the Gospel and cut off from the Church of the Fathers.

The icon reminds the faithful that Christ became man, that the saints have conquered, and that heaven is not far. It shows the faithful what they are to become. It declares that the Kingdom of God is not a myth or a metaphor, but a visible and present reality. It proclaims that the Church is alive, visible, and holy. It silences novelty. It rebukes heresy. It teaches repentance. It glorifies Christ.

Icons belong to the Church. They are not adornments. They are declarations of victory.

Every Heresy Is, at Its Root, a Rejection of the Incarnation

It is often said that heresy is a distortion of the truth, but more specifically, it is a rejection of the Incarnation. Every heresy, when properly examined, is rooted in an attempt to deny or obscure the mystery of God becoming man in Jesus Christ. It is in this core rejection of the truth of the Incarnation that heresy reveals its true nature as an assault on the very foundation of the Christian faith.

Certain gnostic sects and cults seek to deny the fullness of the Incarnation. These cults undermine the very essence of the Incarnation, which is that God became fully man while remaining fully God. The icon stands as a bold confession against this error, for in every true icon, the unity of Christ’s Person is proclaimed through His visible, personal presence.

Arianism, in a similar vein, denies the full divinity of Christ. It posits that the Son of God is a created being, a lesser divine entity, rather than truly co-essential with the Father. Arianism denies that Christ is truly God in the same way that the Father is. The impact of Arianism is a devaluation of Christ’s redemptive work, for if Christ is not fully divine, He cannot redeem humanity fully. The icon rejects this heresy by continually affirming the divinity of Christ—the image we behold in the icon is not a mere man, but God Incarnate, the Word made flesh, as real and present as the original.

Additionally, the icon resists other errors by insisting that Christ, though divine, truly assumed human nature, and that His human body was transformed and glorified without being absorbed or erased. Icons do not depict a divine ghost in human form, but the true, living, breathing humanity of Christ, sanctified and deified by His divine nature.

In our time, some forms of Protestantism have a dangerous tendency to revert to a kind of functional docetism. This term, derived from the heresy of Docetism, suggests that Christ’s materiality was an illusion, that His physical presence in the world was not truly real. In Protestantism’s frequent emphasis on “spirituality” over “materiality,” it effectively denies the continuing material presence of Christ in the life of the Church. The rejection of icons, the rejection of sacred matter, and the minimisation of the sacraments—all of these tendencies in Protestantism lead to a denial of the truth that Christ remains present in His Church, not just spiritually but materially as well. The icon stands firmly against this error, declaring boldly that Christ, in His flesh, remains present in the life of His Body, the Church.

To remove icons from the churches is not an act of piety or simplicity—it is an act of heresy. It is to undermine the visible reality of God made flesh. The icon is not simply a decoration or an optional aesthetic. It is the witness to the continuing truth of the Incarnation in the life of the Church. To cover the face of Christ, to hide His likeness under a veil, in the name of modesty or simplicity, is to make war against the Gospel. For what is the Gospel if not the proclamation of the visible, material reality of God’s intervention in history, the Word made flesh?

In Orthodox theology, the visible and the invisible are not opposed. Christ’s divinity and humanity are not opposing forces but united and revealed in His Person. The icon is the bridge between the visible and the invisible, declaring that the unseen God became visible and tangible, that He dwelt among us, and that He remains with us. To remove the icon is to withdraw from that testimony. It is to revert to a Gnostic or heretical worldview that sees the material world as irrelevant to salvation, as if salvation is a purely spiritual matter with no bearing on the body or the world.

The enemies of icons, in the name of reform or return to an imagined “pure” Christianity, are not reformers—they are destroyers. They seek to destroy the visible witness of the faith handed down once for all to the saints. (Jude 1:3) By rejecting the icon, they sever the link between the visible Church and the Church Triumphant, between the faithful on earth and the saints in heaven. They abandon the fullness of the Incarnation, substituting for it an abstract spirituality that is far removed from the tangible, real presence of Christ. The icon is the living proclamation that the Church is not a mere idea, a set of teachings, or a collection of abstract beliefs. The Church is the Body of Christ, the Bride of the Lamb, and in it, Christ is present, fully, in the flesh. The icon is not a trivial representation; it is the sign of that presence.

The icon stands against every heresy. It declares that Christ came in the flesh, died in the flesh, and rose again in the flesh. It proclaims the eternal truth that the Word became flesh and dwelt among us. (John 1:14) It affirms that the material world is not separate from the work of God in salvation, but is, in fact, redeemed and sanctified by His Incarnation. The icon is not simply a cultural artefact—it is a theological statement. It is a dogmatic confession. To remove it is not an act of humility; it is an act of denial.

To be Orthodox is to honour icons. To reject them is to place oneself outside the mind of the Church. Icons are not a preference. They are a necessity. They preach the Gospel without words. They testify that Christ is come in the flesh. They unite the Church militant with the Church triumphant. They teach us to honour what God has glorified.

Let no one call it idolatry. It is the defence of the Incarnation. Let no one say they are optional. They are upheld by the Councils, the Fathers, and the very Scriptures themselves. And let no one presume to be wiser than the Church.

May God bless you +

Fr. Charles

15 February 2020

Comments are closed.